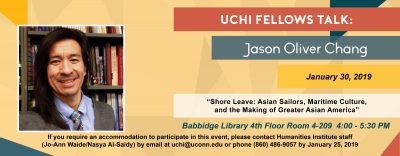

- Tell us a bit about the project you are working on at UCHI.

This project has allowed me to learn a great deal about Asian maritime history and has taught me how little I know. My initial interest in Asian sailors who came to the U.S. but did not become immigrants has opened up a broad inquiry across the Indian Ocean, the archipelagos of southeast Asia and the coastal regions of the South China Sea going back to the seventeenth century. - What drew you to this topic and what exciting developments are you anticipating?

I was very much seduced by the concept of sailors as being estranged from the national and international order, but sailors are difficult to study because they do not leave many records. More importantly, I have found sailors and the maritime world not all together separate from terrestrial and continental histories, but deeply intertwined but often shadowed from each other. - What are you looking forward to in regard to this year at UCHI?

I’m looking forward to finding out how wrong I was about my maritime subject. With a great deal of new research from India, UK, China, Singapore, New Zealand, and the Middle East, I know my earlier conceptions will be altered and that is exciting. - Many people wonder what value the humanities and humanities research has in today’s world. What are your thoughts on what humanities scholarship “brings to table?”

One thing this project has taught me is how regionally diverse, complex, and interlinked seemingly mundane lives can be when put together comparatively. This realization underscores, for me, the enormous value of exploring subjectivity, cultural production, and epistemology in power relations. Not only because it is important to understand the dynamics between the hegemon and subaltern but also to account for, acknowledge, and ward against the erasure of ways of being, ways of signifying, and ways of knowing by those who struggle to be recognized.