The Cambridge History of Ireland

General Editor: Thomas Bartlett

FOR RELEASE on 30 April 2018

Announcing a landmark survey of Irish history from c.600 to the present day

Written by a team of more than 100 leading historians from around the world, this is the most comprehensive and authoritative history of Ireland yet attempted

Vibrant, comprehensive, and accessible, The Cambridge History of Ireland presents the Irish story – or stories – from 600 to the present. Four comprehensive volumes bring together the latest scholarship, setting Irish history within broader Atlantic, European, imperial and global contexts.

The work benefits from a strong political narrative framework, and is distinctive in including essays that address the full range of social, economic, religious, linguistic, military, cultural, artistic and gender history, and in challenging traditional chronological boundaries in a manner that offers new perspectives and insights.

Each volume examines Ireland’s development within a distinct period, and offers a complete and rounded picture of Irish life, while remaining sensitive to the unique Irish experience.

About the Editors

Thomas Bartlett has held positions at the National University of Ireland, Galway, then as Professor of Modern Irish history at University College Dublin, and most recently as Professor of Irish history at the University of Aberdeen, until his retirement in 2014. His previous publications include Ireland: A History (Cambridge, 2010). Brendan Smith is a Professor of Medieval History at the University of Bristol. He is the author and editor of numerous books on medieval Ireland, including several collections of historical documents. Jane Ohlmeyer is Erasmus Smith’s Professor of Modern History at Trinity College, Dublin and the Director of the Trinity Long Room Hub, Trinity’s research institute for advanced study in the Arts and Humanities. Since September 2015 she has also served as Chair of the Irish Research Council. Professor Ohlmeyer is the author/editor of eleven books, including Making Ireland English: The Aristocracy in Seventeenth-Century Ireland (2012). James Kelly is Professor of History at Dublin City University and President of the Irish Economic and Social History Society. His many publications include Sport in Ireland, 1600–1840 (2014), which won the special commendation prize offered by the National University of Ireland in 2016.

More information on the individual volumes

The first volume of The Cambridge History of Ireland presents the latest thinking on key aspects of the medieval Irish experience, focusing on the extent to which developments were unique to Ireland. The openness of Ireland to outside influences, and its capacity to influence the world beyond its shores, are recurring themes. Underpinning the book is a comparative, outward-looking approach that sees Ireland as an integral but exceptional component of medieval Christian Europe.

Volume Two looks at the transformative and tumultuous years between 1550 and 1730, offering fresh perspectives on the political, military, religious, social, cultural, intellectual, economic, and environmental history of early modern Ireland. As with all the volumes in the series, contributors here situate their discussions in global and comparative contexts.

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was an era of continuity as well as change. Though properly portrayed as the era of ‘Protestant Ascendancy’, it embraces two phases – the eighteenth century when that ascendancy was at its peak; and the nineteenth century when the Protestant elite sustained a determined rear-guard defence in the face of the emergence of modern Catholic nationalism. This volume moves beyond the familiar political narrative to engage with the economy, society, population, emigration, religion, language, state formation, culture, art and architecture, and the Irish abroad

The final volume in the Cambridge History of Ireland covers the period from the 1880s to the present. This insightful interpretation on the emergence and development of Ireland during these often turbulent decades is copiously illustrated, with special features on images of the ‘Troubles’ and on Irish art and sculpture in the twentieth century.

Volume 1. 600–1550

Brendan Smith, Editor

9781107110670

674 Pages

Volume 2. 1550–1730

Jane Ohlmeyer, Editor

9781107117631

808 Pages

Volume 3. 1730–1880

James Kelly, Editor

9781107115200

862 Pages

Volume 4. 1880 to the Present

Thomas Bartlett, Editor

9781107113541

952 Pages

Each Volume

£100.00 $130.00 €116.71

Four Volume Set

9781107167292

2800 Pages

£350.00 $475.00 €408.49

For a full list of contributors to each volume, visit www.cambridge.org

For an author interview or more information please contact

Amy F Lee at Cambridge University Press: aflee@cambridge.org

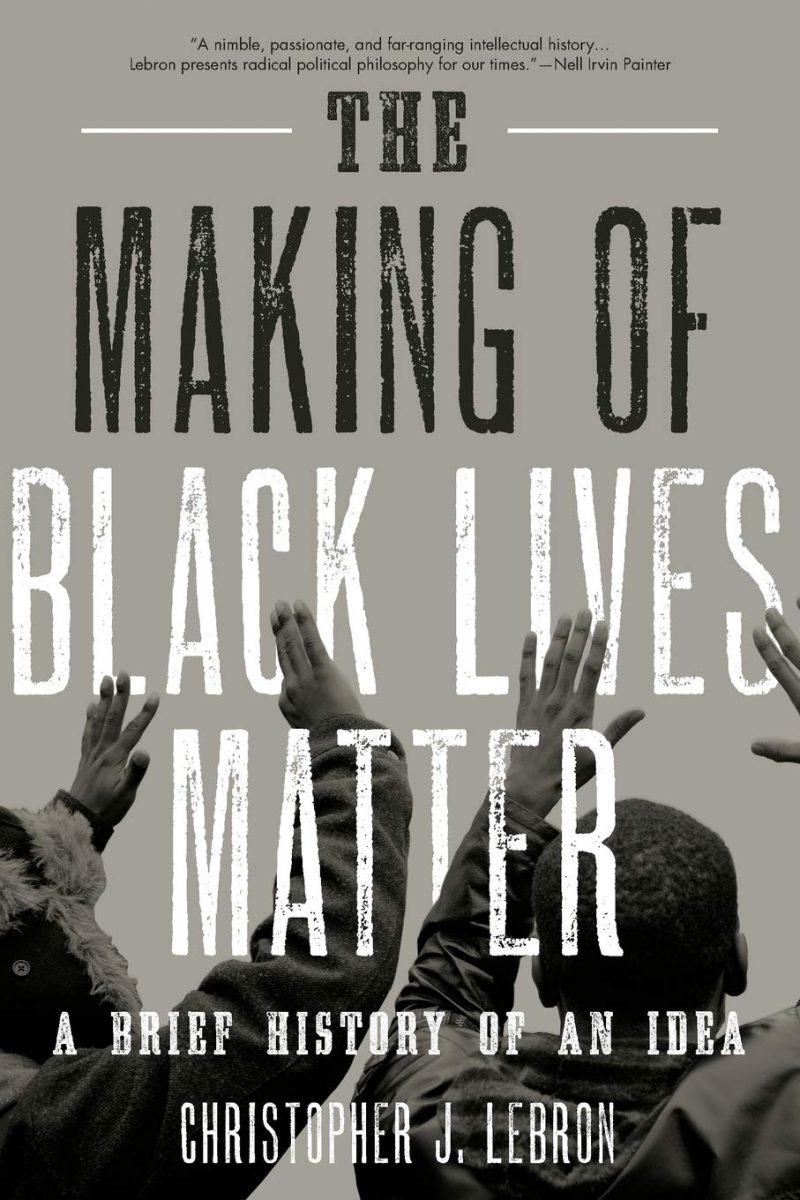

“‘What you should read, see, and hear?’ You should read The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea (Oxford University Press, 2017) by political theorist, Christopher J. Lebron, because he reminds us that the philosophical underpinnings of the #BlackLivesMatter movement predate the contemporary movement. Analyzing the treatment of “Black” people over time, Lebron submits a historical framing of Black political thinkers’, activists,’ and letterpersons’ understandings about Black people’s rights (and the lack, thereof) in American society. This treatment, Lebron notes, prompted Black Americans’ rhetorical, oratorical, lettered, and physical activism to articulate and assert Black people’s equal humanity, rights, and protection in different eras of American political history. Thus, Lebron outlines the tradition of Black resistance oriented in the long-standing Black freedom struggle to contest racial discrimination and systemic inequality in various forms (in addition to contemporary struggles against police brutality). Lebron elucidates this longitudinal activism by examining political thought and expressions of Black men and women, such as Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Audre Lorde, Anna Julia Cooper, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who establish foundational arguments about Black Americans’ humanity, (in)justice, and liberation for various iterations of “Black,” intersectional identities (class, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity, for example).”

“‘What you should read, see, and hear?’ You should read The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea (Oxford University Press, 2017) by political theorist, Christopher J. Lebron, because he reminds us that the philosophical underpinnings of the #BlackLivesMatter movement predate the contemporary movement. Analyzing the treatment of “Black” people over time, Lebron submits a historical framing of Black political thinkers’, activists,’ and letterpersons’ understandings about Black people’s rights (and the lack, thereof) in American society. This treatment, Lebron notes, prompted Black Americans’ rhetorical, oratorical, lettered, and physical activism to articulate and assert Black people’s equal humanity, rights, and protection in different eras of American political history. Thus, Lebron outlines the tradition of Black resistance oriented in the long-standing Black freedom struggle to contest racial discrimination and systemic inequality in various forms (in addition to contemporary struggles against police brutality). Lebron elucidates this longitudinal activism by examining political thought and expressions of Black men and women, such as Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Audre Lorde, Anna Julia Cooper, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who establish foundational arguments about Black Americans’ humanity, (in)justice, and liberation for various iterations of “Black,” intersectional identities (class, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity, for example).”