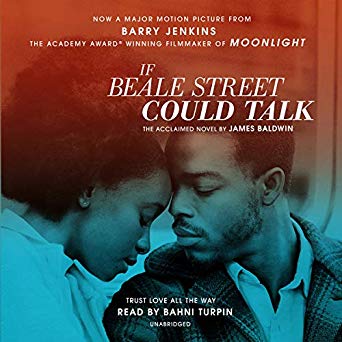

"You should read James Baldwin's 1974 novel If Beale Street Could Talk and view Barry Jenkins's 2018 film adaptation of Baldwin's novel.

A deeply affecting love story, Baldwin's novel centers on a young couple, Tish and Fonny. When the novel opens, Fonny is in jail accused of a crime he did not commit and Tish reveals she is pregnant. The romance is infused with an all-too-timely critique of systematic racism in the American criminal justice system. As he often did, Baldwin broke conventions and sparked controversy with this novel, choosing to tell the story from the perspective of its young black female protagonist. Poet and activist June Jordan wrote a scathing review of Baldwin's appropriation of the young black female voice. A daring, complex, and thought-provoking work of sustaining black love, If Beale Street Could Talk demonstrates Baldwin's continued relevance in these times.

Director Barry Jenkins has now adapted Baldwin's novel to the screen, following up his Academy Award-winning Moonlight (recently recommended here by my colleague Professor Melina Pappademos). You should read the book and watch the film, because although the film is largely faithful to the book, even a filmmaker as skilled as Jenkins leaves a lot on the page. Those who view the film only will miss some of the work's thematic power (as well as a major element of the story's finale).

You'll also be voting with your entertainment dollars for more such adaptions of Baldwin's work and the work of other African American writers. We've recently seen a flurry of successful film adaptations of African American literature: the adaption of August Wilson's Fences starring Denzel Washington and Viola Davis, Steve McQueen's adaptation of Solomon Northup's Twelve Years a Slave, and last year's The Hate U Give based on the Young Adult novel by Angie Carter, just to name a few. The success of Beale Street -- Regina King has already won a Golden Globe for her performance as Sharon Rivers -- and Raoul Peck's Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro may promise more cinematic representations of Baldwin's work. And I could easily list several dozen other works in the African American literary canon that would make excellent and timely material for feature-length film treatment.

There are other movies that will get much more attention, but you should see If Beale Street Could Talk. It's a superhero movie."

- Shawn Salvant

Associate Professor of English and Africana Studies

University of Connecticut