If you require accommodation to attend this event, please contact us at uchi@uconn.edu or by phone (860) 486-9057. We can request ASL interpreting, computer-assisted real time transcription, and other accommodations offered by the Center for Students with Disabilities.

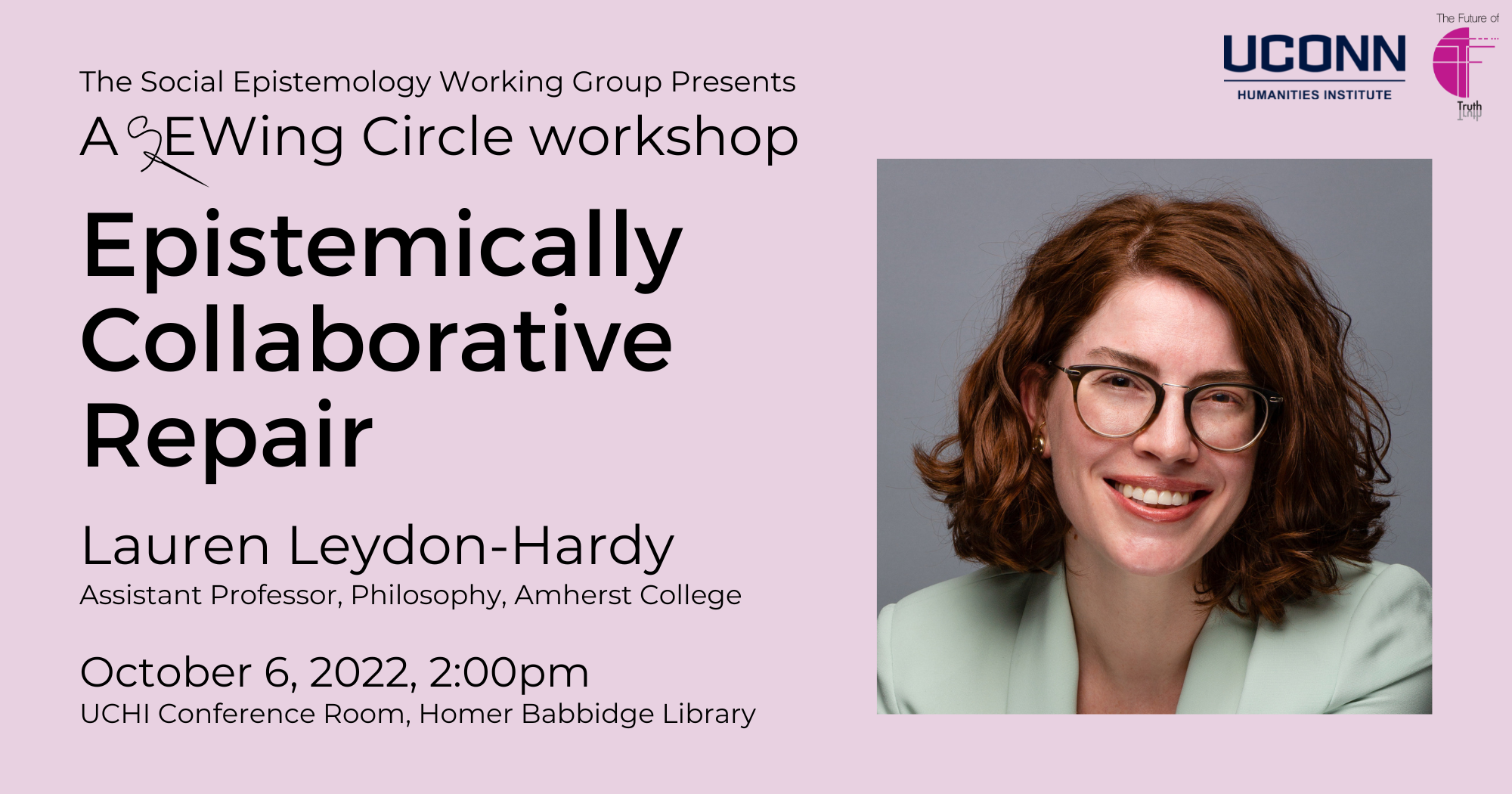

The Social Epistemology Working Group presents:

A SEWing Circle Workshop

Epistemically Collaborative Repair

Lauren Leydon-Hardy

October 6, 2022, 2:00pm

Homer Babbidge Library, Humanities Institute Conference Room

This event will also be livestreamed with automated captioning. Register to attend virtually.

Many epistemologists have been dubious of the idea of epistemic obligation. For a discipline that often understands itself as beginning with the perennial problem of skepticism, it isn’t hard to see why this would be: if I could be a recently envatted brain, or if I may now be massively deceived by an evil demon, then surely there is nothing that I am obliged to believe—not even that here is a hand. Recently, Jennifer Lackey (2021) has argued not only that we have epistemic duties, but that our epistemic duties pertain to both our doxastic and our practical lives; to what we ought to believe, and to how we ought to conduct ourselves qua epistemic agents. Moreover, she argues that our epistemic duties might be other regarding. Beyond my obligation to believe in accordance with my evidence, I may also have epistemic obligations to you. On this view, positive interpersonal epistemic obligations will include the promotion of various epistemic goods, while negative interpersonal epistemic obligations will involve the prevention of epistemic wrongs or harms. More recently still, Lackey has also developed a framework for thinking about epistemic reparations, which she understands to be: “Intentionally reparative actions in the form of epistemic goods given to those epistemically wronged by parties who acknowledge these wrongs and whose reparative actions are intended to redress them.” On this framework, certain kinds of experiences have distinctively epistemic dimensions. These include “gross violation[s] or injustice[s],” which specifically give rise to “the right to be known, and the corresponding duty to see, hear, and bear witness—to know.” This kind of knowing, which involves bearing witness, is epistemically reparative work. In this paper I explore a particular type of epistemically reparative work. I call this epistemically collaborative repair and suggest that the need for epistemically collaborative repair arises from a particularly thorny type of epistemic obligation to the self. These obligations involve acquiring difficult or challenging articles of self-knowledge, for example, that one has been a victim of child sexual abuse, or that one has been predatorily groomed. Sometimes, we owe it to ourselves to understand what happened to us. And sometimes, we cannot do that alone, through recollection or rumination on the details of our experiences. Instead, I argue that discharging this self-regarding epistemic obligation might only be possible through the satisfaction of another person’s corresponding right to be known. These are cases where an epistemic agent’s route to understanding their first-personal experience is in and through the epistemic work of ‘bearing witness’ in Lackey’s sense. Thus, it is in this act of epistemic service that one may come to learn their own truth, discharging their own, self-regarding epistemic duty through essentially collaborative epistemic repair.

Lauren Leydon-Hardy is an assistant professor at Amherst College, Department of Philosophy. Her research program is centered around the norms that govern our social world and how those norms shape our epistemic lives.