The University of Connecticut Humanities Institute (UCHI) is proud to announce its incoming class of humanities fellows. We are excited to host four dissertation scholars (including the Draper Dissertation Fellow and the Richard Brown Dissertation Fellow), four undergraduate fellows, nine faculty fellows (including the Faculty of Color Working Group Fellow), and three external fellows. We have fellows representing a broad swath of disciplines, including History; English; Anthropology; Philosophy; Political Science; Geography; Digital Media and Design; Literatures, Culture and Languages; Journalism; Law; Africana Studies; and American Studies. Their projects take many forms including scholarly monographs, short story collections, and feature-length films; and they cover topics from women’s activism, to human rights, to Indigenous literacies. For more information on our fellowship program see our Become a Fellow page. Welcome fellows!

Visiting Fellows

Jordan Camp (American Studies, Trinity College)

“The Southern Question”

Alexander Diener (Geography, University of Kansas)

“The Middle of Somewhere: Place Attachment and the Geographies of Being”

Birgit Brander Rasmussen (English, SUNY Binghamton)

“Signs of Resistance, Signs of Resurgence: Indigenous Literacies, New Media, and Anti-Colonial Imaginaries in Native American Literature and Culture”

Undergraduate Fellows

Breanna Bonner (Project advisor: Evelyn Simien)

“‘The Space Between Black and Liberation’: Analyzing Black Women’s Experiences of Intersectional Invisibility Within Liberation Movements”

Annabelle Bergstrom (Project advisor: Julian J. Schlöder)

“Minds Among Minds: A Pragmatist View of the Social and Spiritual Self in a Hyperconnected World”

Brent Freed (Project advisor: Elizabeth Della Zazzera)

“A Revolution Hijacked: Art and Ideology from the Atelier Populaire”

Nathan Howard (Project advisor: Tracy Llanera)

“Homofascism: The Queering of Hate”

Honorable mention: Gianna Socci, “Monstrosity on Trial: Claiming Legal Personhood for Frankenstein’s Monster”

Dissertation Research Scholars

Kathryn Angelica (History)

Draper Dissertation Fellow

“An Uneasy Alliance: Cooperation and Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Black and White Women’s Activism”

David Evans (History)

“Hunger for Rights: Establishing the Human Right to Food, 1930—1988”

Geoffrey Hedges-Knyrim (Anthropology)

“Political Power during the Iron Age of the Southern Levant Through the Lens of Agricultural Production”

Xu Peng (Literatures, Culture, and Languages)

Richard Brown Dissertation Fellow

“From History to the Future: Chineseness in Contemporary Cuban, Puerto Rican and Dominican Literatures and Cultures”

UConn Faculty Fellows

Zehra Arat (Political Science)

“Human Rights Norms in Turkey”

Ana María Díaz-Marcos (Literatures, Culture, and Languages)

“‘A fistful of antifascist energy’: Ernestina Gonzalez Fleischman’s Biography and Writings”

Katerina Gonzalez Seligmann (Literatures, Culture, and Languages & El Instituto)

“Soliarity in Translation: Aimé Césaire and His Cuban Comrades in Art”

Serkan Gorkemli (English)

“You’re Always Welcome Here, a Book of Short Stories”

Martine Granby (Journalism & Africana Studies)

Faculty of Color Working Group Fellow

“Ten Seconds of Sugar”

Oscar Guerra (Digital Media and Design)

“Documenting Mental Health in Migration”

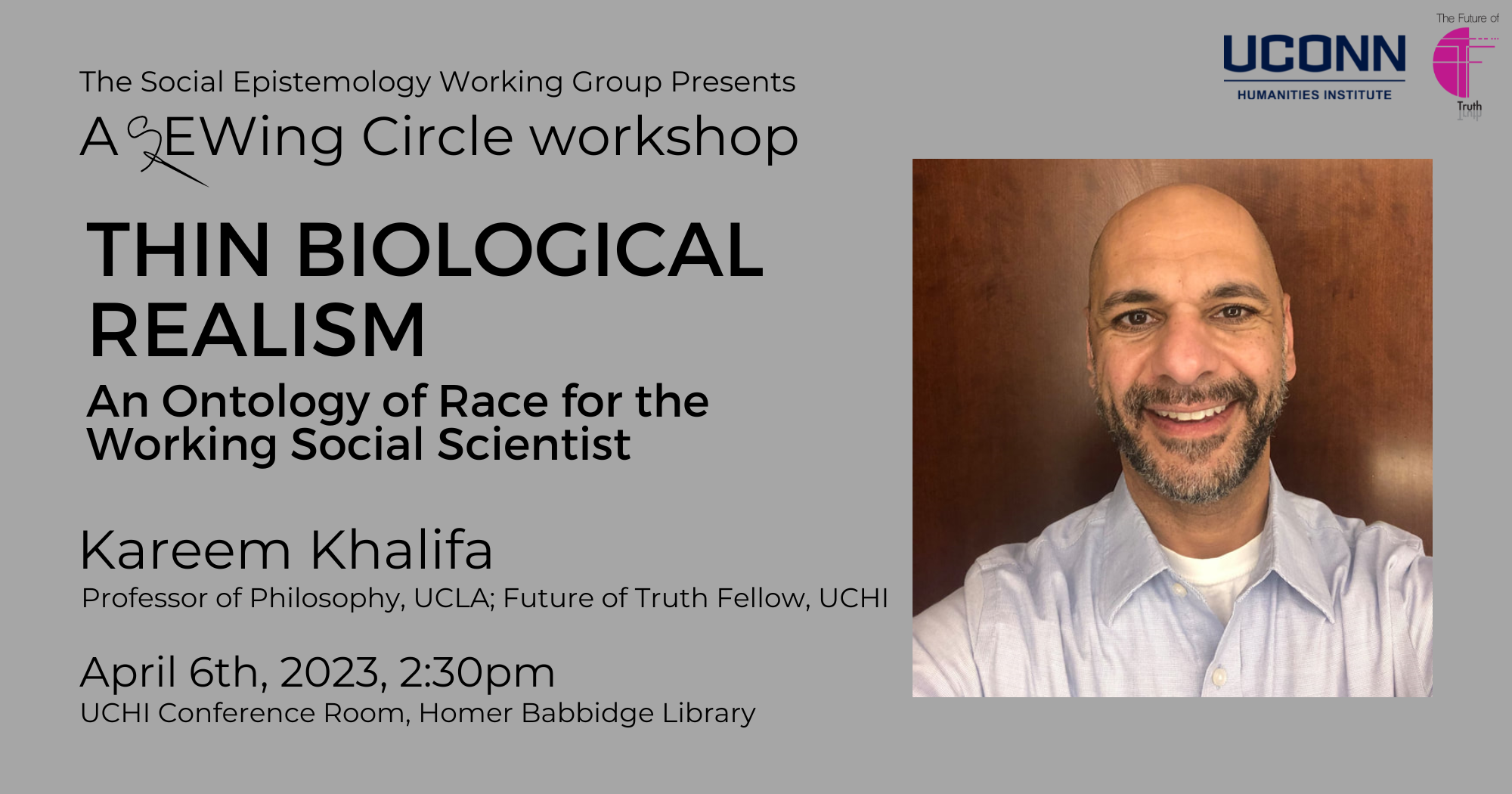

Tracy Llanera (Philosophy)

“The Misfits of Extremism”

Richard Wilson (Law)

“United Against Hate? Punishing Bias Crimes in the United States”

Victor Zatsepine (History)

“Unsettling the Sino-Mongol-Russian Borderlands, 1911–1945”