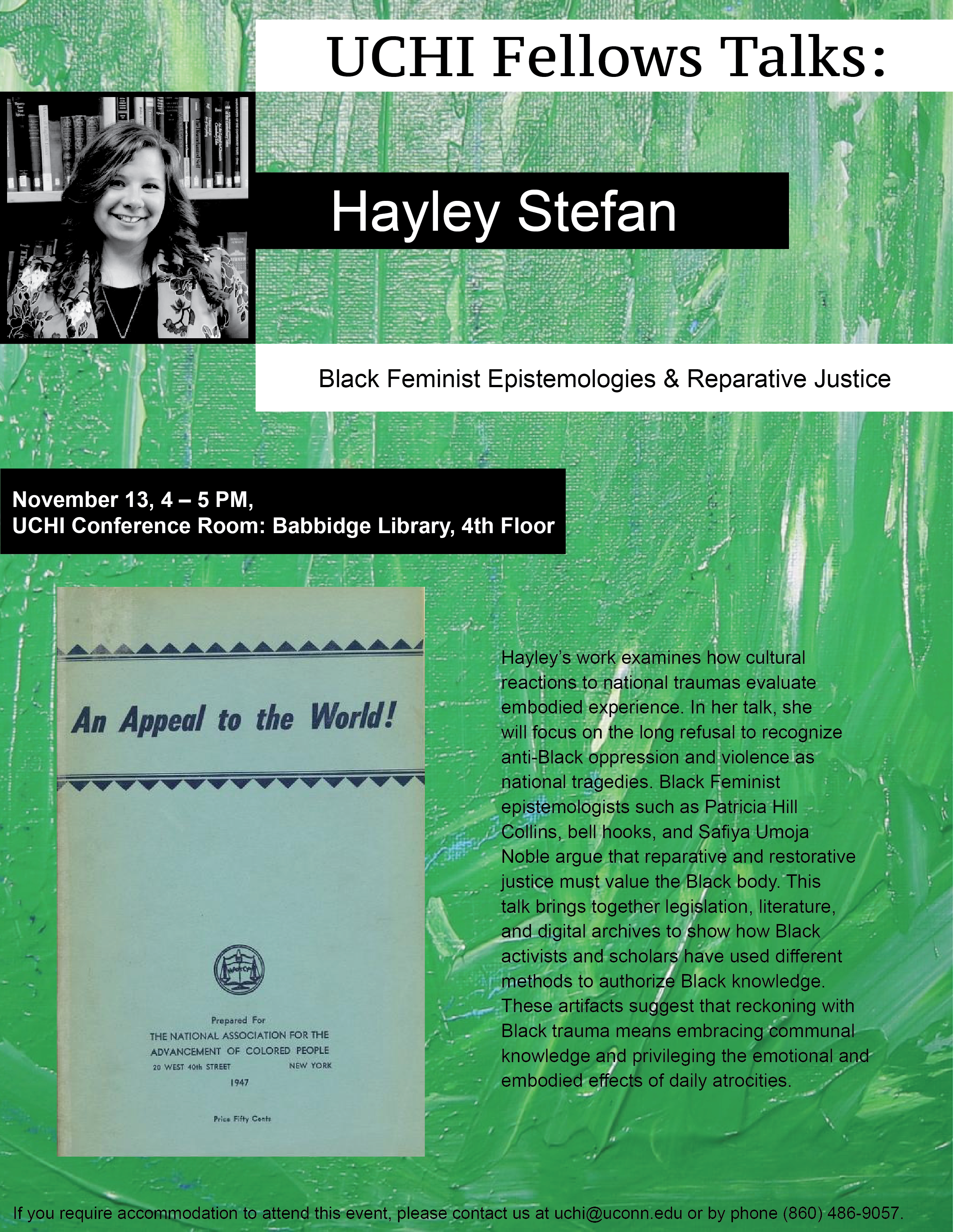

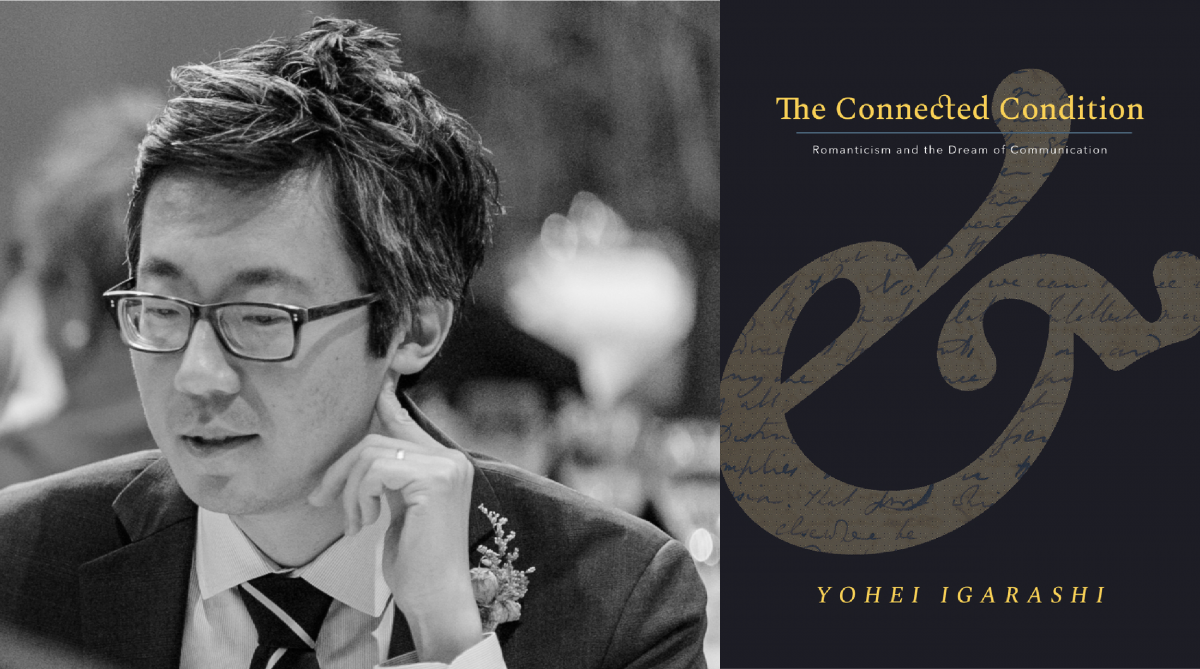

Yohei Igarashi, the Assistant Director of Digital Humanities and Media Studies at the University of Connecticut Humanities Institute (UCHI) is the author of a new book entitled The Connected Condition: Romanticism and the Dream of Communication (Stanford University Press). According to the website of the publisher, “the Romantic poet’s intense yearning to share thoughts and feelings often finds expression in a style that thwarts a connection with readers. Yohei Igarashi addresses this paradox by reimagining Romantic poetry as a response to the beginnings of the information age. Data collection, rampant connectivity, and efficient communication became powerful social norms during this period. The Connected Condition argues that poets responded to these developments by probing the underlying fantasy: the perfect transfer of thoughts, feelings, and information, along with media that might make such communication possible.” Igarashi, also an associate professor of English at UConn, has authored many articles on Romanticism and poetry, including in New Literary History, Romantic Circles, and Studies in Romanticism; the latter of which received the Keats-Shelley Association of America annual essay prize in 2015.

Who is Victoria Ford Smith?

Who is Victoria Ford Smith?

You should listen to Regina Spektor’s music — but only if you’re ready for a brush with genius. Wild genius, that is, skyrocketing musically through the magical, heartbreaking, infuriating, absurd journey that is life. Nothing is lyrically off limits for Spektor —

You should listen to Regina Spektor’s music — but only if you’re ready for a brush with genius. Wild genius, that is, skyrocketing musically through the magical, heartbreaking, infuriating, absurd journey that is life. Nothing is lyrically off limits for Spektor —  Who is Sarah Willen?

Who is Sarah Willen?