This event will include automated captioning. If you require accommodation to attend this event, please contact us at uchi@uconn.edu or by phone (860) 486-9057. We can request ASL interpreting, computer-assisted real time transcription, and other accommodations offered by the Center for Students with Disabilities.

The Digital Humanities and Media Studies Initiative presents:

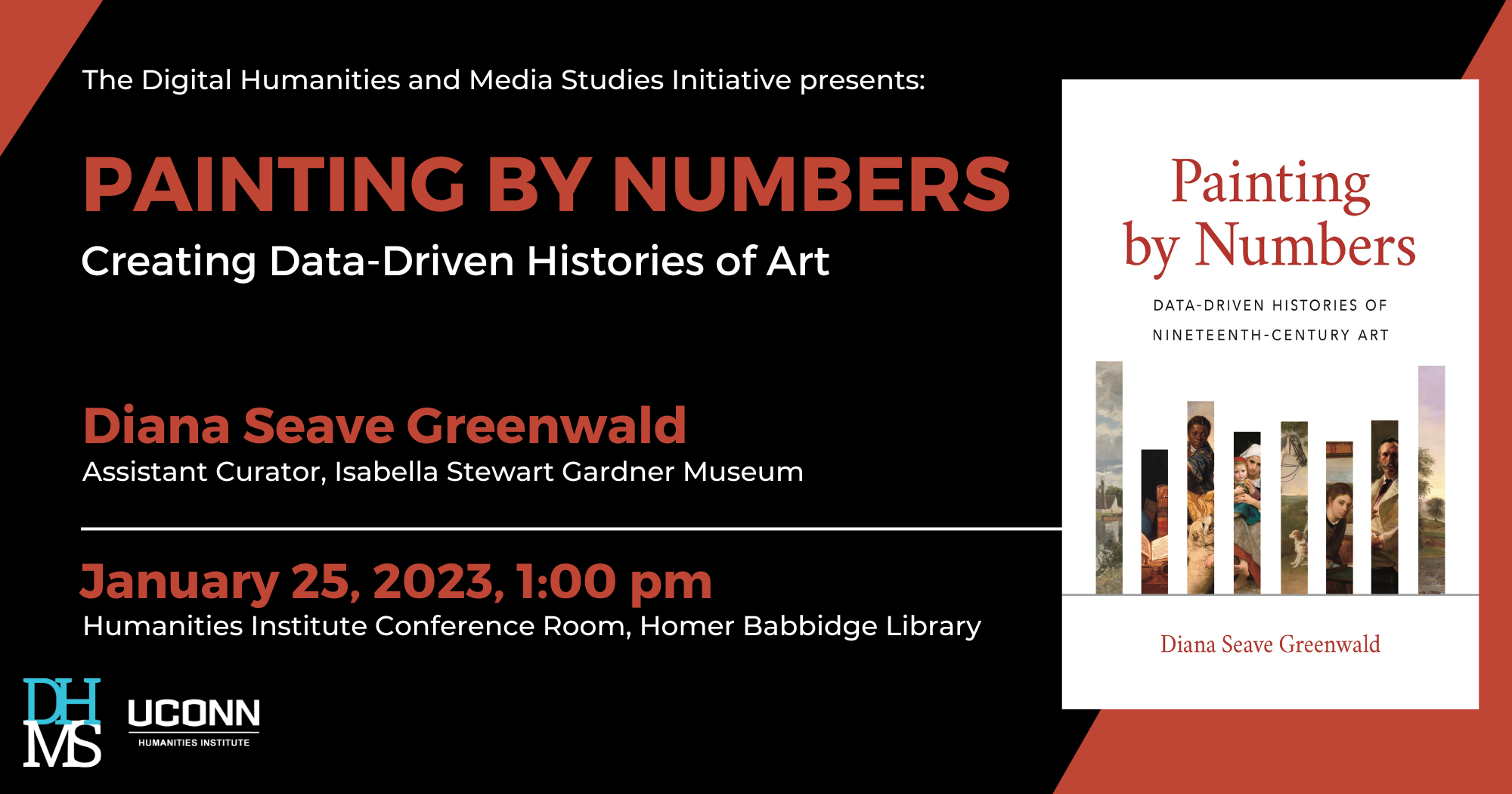

Painting by Numbers: Creating Data-Driven Histories of Art

Diana Seave Greenwald

January 25, 2022, 1:00pm

Live. Online. Registration required.

Add to Google calendar Add to Office 365 calendar Add to other calendar

This talk presents how one can blend historical and social scientific methods to provide fresh insights into nineteenth-century art. It describes the extent to which art historians have focused on a limited—and potentially biased—sample of artwork from that time. With new quantitative evidence for more than five hundred thousand works of art, one can address long-standing art historical questions about the effects of industrialization, gender, and empire on the art world.

In particular, this presentation focuses on a case study that combines theory from labor economics with data about works by nineteenth-century women artists. It examines how women artists’ domestic responsibilities forced them to be active in certain genres and media—particularly still-life paintings and watercolors—that are faster to finish and can be completed on a more flexible schedule. This insight about how artistic form and content change in response to demands on women’s time highlights structural barriers that still hamper nineteenth-century women artists’ posthumous reputations and continue to limit women artists’ attainment today.

Diana Seave Greenwald is an art historian and economic historian. Her work uses both statistical and qualitative analyses to explore the relationship between art and broader social and economic change during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly in the United States and France. Her first book, Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth Century Art, was published by Princeton University Press in 2021.

Diana is currently the William and Lia Poorvu Interim Curator of the Collection at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Prior to joining the Gardner, she was an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., working in the departments of American ansd British Paintings and Modern Prints and Drawings.

She received a D.Phil. in History from the University of Oxford. Before doctoral study, Diana earned an M.Phil. in Economic and Social History from Oxford and received a Bachelor’s degree in Art History from Columbia University.