In celebration of 20 years of UCHI and as part of our ongoing You Should… series, we’ve asked former fellows and other friends of the Institute to recommend something related to their work or process. Read them all here.

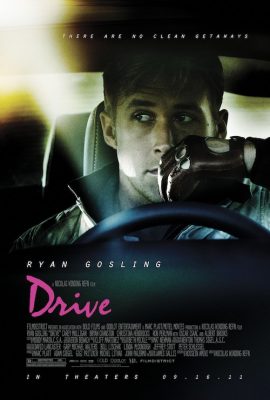

Drive (2011) is a movie about boundaries and boundaries blurred—between day and night, between the criminal world and the world of bystanders, between moments of tenderness and—fair warning—moments of intense violence.

Drive (2011) is a movie about boundaries and boundaries blurred—between day and night, between the criminal world and the world of bystanders, between moments of tenderness and—fair warning—moments of intense violence.

The protagonist is a Hollywood stuntman / criminal getaway specialist credited only as “Driver.” He speaks in short, staccato bursts. He communicates mostly to set limits to his interactions with others, such as the petty criminals to whom he disdainfully lends his expertise.

His obligations are fleeting—a five-minute window where “anything happens, and I’m yours.” A tick of the clock either side of those five minutes: “you’re on your own.” Each dictation of terms ends with a rhetorical “do you understand?” Driver doesn’t want an answer, the question is purely to reinforce the limits of his engagement with his environment.

And that environment—a neon-lit nighttime Los Angeles, beautifully framed by director Nicholas Winding Refn—is viewed from the margins by Driver. In the James Sallis novella that provides the source material, we are told that Driver “existed a step or two to one side of the common world, largely out of sight, a shadow, all but invisible.” He prizes anonymity, taking short-term leases on nondescript apartments, forming no ties, collecting no baggage, ready to leave on a moment’s notice.

But chance intervenes and soon Driver is no longer setting the terms of his engagement with the world.

Listen for the strange alchemy of the soundtrack. The anthem “A Real Hero” captures the soul of the story with its double-edged refrain “a real human being, and a real hero.” The track which plays over the opening credit, “Night Call,” sets the dark tone; the Chromatics’ “Tick of the Clock” accents the precision of Driver’s craft; the glorious torch-song “Oh My Love” is deeply moving in context.

Note too the way that heroic archetypes are skillfully deployed: The man with no name, the cowboy who rides into town to solve problems then rides off into the sunset, the road-warrior of the Mad Max series. But this is an anti-hero tale at its dark heart. Driver is a violent man and the world in which he operates is brutally Darwinian.

Drive then is a contemporary noir about a man who has carefully constructed a context in which he can function. The question is what happens when the boundaries he has drawn for himself are, suddenly, erased. Who, in the end, is Driver—a real hero, or a somewhat shabby and fallen human being?

– Stephen Dyson

Professor of Political Science

University of Connecticut

Who is Stephen Dyson? Stephen Dyson is Professor of Political Science at the University of Connecticut. He received his Ph.D. from Washington State University in 2004. His scholarly work focuses on representations of politics and international relations in popular culture, particularly science fiction, and on elite decision making in foreign policy. He teaches classes on politics and popular culture, international relations, political leadership, and the history of nuclear weapons.

Who is Stephen Dyson? Stephen Dyson is Professor of Political Science at the University of Connecticut. He received his Ph.D. from Washington State University in 2004. His scholarly work focuses on representations of politics and international relations in popular culture, particularly science fiction, and on elite decision making in foreign policy. He teaches classes on politics and popular culture, international relations, political leadership, and the history of nuclear weapons.

Who is Manisha Desai? Manisha Desai is Professor of Sociology and Asian and Asian American Studies at the University of Connecticut. Committed to decolonizing knowledge and social justice, her research and teaching interests include Gender and Globalization, Transnational Feminisms and women’s movements, Human Rights movements, and Contemporary Indian Society. Currently, she’s working on a book manuscript on the Changing Contours of the Women’s Movement in India. Based on nine months of ethnographic research, funded by the American Institute of India Studies Senior Fellowship, she examines the new articulations of women’s activism with Dalit struggles, Anti-Communalism, and the rural and urban crises of neoliberal policies for the marginalized. Her forthcoming publication with Rianka Roy, Krantijyoti Gyanjyoti Savitribai: The Light of Revolution and Knowledge is the start of a new project on what she calls “the second decolonial moment,” in the Global North and South, to bring the work of 19th century Dalit theorist Savitribai Phule and her collaborators in the Satya Shodhak Samaj (the Society of Truth Seekers) to a larger audience.

Who is Manisha Desai? Manisha Desai is Professor of Sociology and Asian and Asian American Studies at the University of Connecticut. Committed to decolonizing knowledge and social justice, her research and teaching interests include Gender and Globalization, Transnational Feminisms and women’s movements, Human Rights movements, and Contemporary Indian Society. Currently, she’s working on a book manuscript on the Changing Contours of the Women’s Movement in India. Based on nine months of ethnographic research, funded by the American Institute of India Studies Senior Fellowship, she examines the new articulations of women’s activism with Dalit struggles, Anti-Communalism, and the rural and urban crises of neoliberal policies for the marginalized. Her forthcoming publication with Rianka Roy, Krantijyoti Gyanjyoti Savitribai: The Light of Revolution and Knowledge is the start of a new project on what she calls “the second decolonial moment,” in the Global North and South, to bring the work of 19th century Dalit theorist Savitribai Phule and her collaborators in the Satya Shodhak Samaj (the Society of Truth Seekers) to a larger audience. Transgression has long been a watchword for avant-garde artistic practices. Since the days of Marcel Duchamp, artists have found a critical power in simultaneously claiming a hard-won autonomy and, paradoxically, striving to break down its self-imposed borders. But what happens when the meaning of boundaries changes? When the tactics of aesthetic disobedience used to escape the autonomous artwork’s hermetic self-referentiality increasingly produce only “second-rate transgressions that change nothing” (xvii)? When art becomes part of a planetary integration that is experienced asymmetrically and unequally?

Transgression has long been a watchword for avant-garde artistic practices. Since the days of Marcel Duchamp, artists have found a critical power in simultaneously claiming a hard-won autonomy and, paradoxically, striving to break down its self-imposed borders. But what happens when the meaning of boundaries changes? When the tactics of aesthetic disobedience used to escape the autonomous artwork’s hermetic self-referentiality increasingly produce only “second-rate transgressions that change nothing” (xvii)? When art becomes part of a planetary integration that is experienced asymmetrically and unequally? Who is Robin Greeley? Robin Greeley is Associate Professor of Modern & Contemporary Latin American Art History at UConn. Dr. Greeley received her S.M.Arch.S. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1988), and her Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley (1996). Dr. Greeley has authored, edited and co-edited a number of books, most recently, La Interculturalidad y sus imaginarios. Conversacionces con Néstor García Canclini (Gedisa, 2018). She is a founding member of the Symbolic Reparations Research Project.

Who is Robin Greeley? Robin Greeley is Associate Professor of Modern & Contemporary Latin American Art History at UConn. Dr. Greeley received her S.M.Arch.S. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1988), and her Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley (1996). Dr. Greeley has authored, edited and co-edited a number of books, most recently, La Interculturalidad y sus imaginarios. Conversacionces con Néstor García Canclini (Gedisa, 2018). She is a founding member of the Symbolic Reparations Research Project. UConn Professor Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar’s

UConn Professor Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar’s  Who is Amanda Douberley? Amanda Douberley is Assistant Curator/Academic Liaison at the William Benton Museum of Art, where she is responsible for connecting the Benton’s collections and exhibitions with teaching in departments across the university. She has curated numerous exhibitions at the museum, often in collaboration with faculty and other campus partners. Amanda holds a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin with a focus on 20th-century American sculpture and public art. Before coming to UConn in 2018, she taught in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

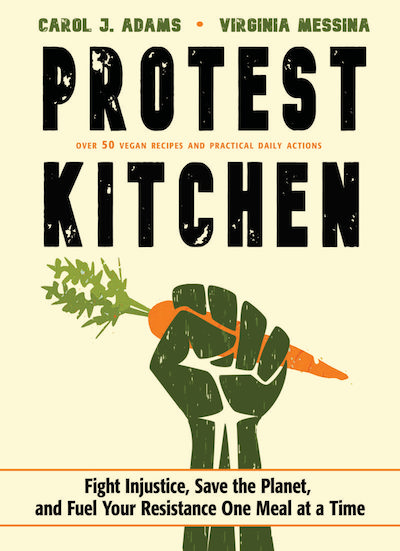

Who is Amanda Douberley? Amanda Douberley is Assistant Curator/Academic Liaison at the William Benton Museum of Art, where she is responsible for connecting the Benton’s collections and exhibitions with teaching in departments across the university. She has curated numerous exhibitions at the museum, often in collaboration with faculty and other campus partners. Amanda holds a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin with a focus on 20th-century American sculpture and public art. Before coming to UConn in 2018, she taught in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In the midst of a global pandemic, with its attendant periods of isolation and restrictions on social gatherings, many have been spending more time in the kitchen than usual. In the midst of racially motivated violence, police brutality, and the push towards a public reckoning with America’s racist history, many have been seeking new and potentially transformative modes of political engagement. In the midst of an on-going climate crisis and the failure of governments to make the necessary choices to save the planet and fight environmental injustice, many of us may find it easy to feel disheartened and powerless.

In the midst of a global pandemic, with its attendant periods of isolation and restrictions on social gatherings, many have been spending more time in the kitchen than usual. In the midst of racially motivated violence, police brutality, and the push towards a public reckoning with America’s racist history, many have been seeking new and potentially transformative modes of political engagement. In the midst of an on-going climate crisis and the failure of governments to make the necessary choices to save the planet and fight environmental injustice, many of us may find it easy to feel disheartened and powerless. Who is Drew Johnson? Drew Johnson is a Ph.D. student (ABD) in the philosophy department at the University of Connecticut. His research focuses on metaethics and epistemology. His dissertation proposes a theory of ethical thought and discourse that explains the distinctive action-guiding, affective, and expressive dimensions of ethical claims and judgments, while also recognizing the important semantic, logical, and epistemological continuities that exist between ethics and other factual domains. In epistemology, Drew’s research focuses on the rational standing of our most firmly held commitments, i.e., our “hinge” commitments upon which all rational evaluation turns.

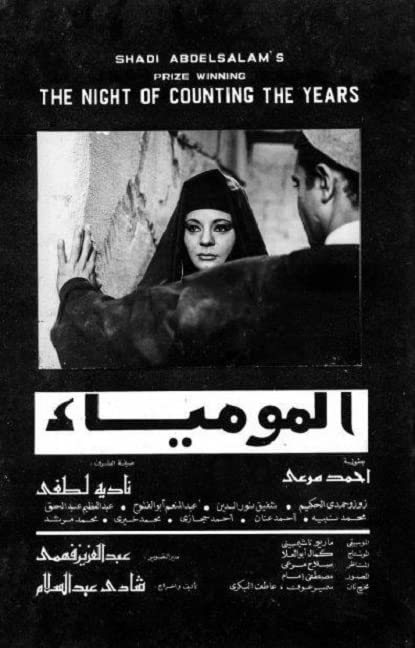

Who is Drew Johnson? Drew Johnson is a Ph.D. student (ABD) in the philosophy department at the University of Connecticut. His research focuses on metaethics and epistemology. His dissertation proposes a theory of ethical thought and discourse that explains the distinctive action-guiding, affective, and expressive dimensions of ethical claims and judgments, while also recognizing the important semantic, logical, and epistemological continuities that exist between ethics and other factual domains. In epistemology, Drew’s research focuses on the rational standing of our most firmly held commitments, i.e., our “hinge” commitments upon which all rational evaluation turns. Based on the true story of an early discovery in the Valley of the Kings and Queens in Luxor, the burial site of successive ancient Egyptian Pharaohs,

Based on the true story of an early discovery in the Valley of the Kings and Queens in Luxor, the burial site of successive ancient Egyptian Pharaohs,  Who is Hind Ahmed Zaki? Hind Ahmed Zaki is an Assistant Professor of Political Science, with a joint appointment in the department of Language, Culture, and Literature. She is specialist in comparative politics with a special emphasis in gender and politics and the Middle East and North Africa. Her research focuses on theories of state feminism, feminist movements, gender-based violence, and qualitative research methods. Her current book project focuses on the politics of women’s rights in Egypt and Tunisia in the period following the Arab spring.

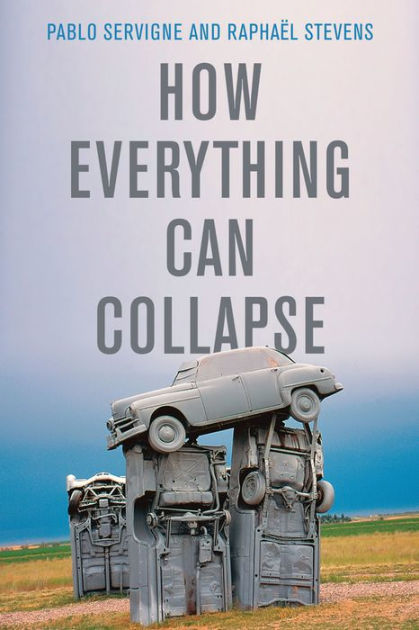

Who is Hind Ahmed Zaki? Hind Ahmed Zaki is an Assistant Professor of Political Science, with a joint appointment in the department of Language, Culture, and Literature. She is specialist in comparative politics with a special emphasis in gender and politics and the Middle East and North Africa. Her research focuses on theories of state feminism, feminist movements, gender-based violence, and qualitative research methods. Her current book project focuses on the politics of women’s rights in Egypt and Tunisia in the period following the Arab spring. “Overindulging in this [message board] may be detrimental to your mental health. Anxiety and depression are common reactions when studying collapse,” warn the moderators of a Reddit message board bluntly titled “

“Overindulging in this [message board] may be detrimental to your mental health. Anxiety and depression are common reactions when studying collapse,” warn the moderators of a Reddit message board bluntly titled “ Who is Daniel Pfeiffer? Daniel Pfeiffer is a Ph.D. candidate in UConn’s English Department and a research assistant at the UConn Humanities Institute. He is writing his dissertation on the New York City art novel after the creative economic turn.

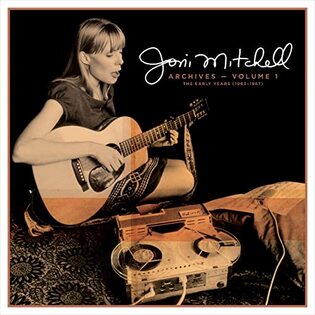

Who is Daniel Pfeiffer? Daniel Pfeiffer is a Ph.D. candidate in UConn’s English Department and a research assistant at the UConn Humanities Institute. He is writing his dissertation on the New York City art novel after the creative economic turn. Prior to her debut album release Song to a Seagull in March 1968, the Archives provides a fascinating chronicle of Joni Mitchell’s development as singer, guitarist, and above all, songwriter. Comprised of radio and television broadcasts, club dates, and home recordings on 5 CDs, we witness her transformation from folksinger of traditional and authored songs (“House of the Rising Sun,” Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee”) to becoming one of the greatest singer-songwriters of the 20th century. The collection includes early versions of iconic songs like “Urge for Going,” “Chelsea Morning, “Both Sides Now,” and “The Circle Game,” as well as over 25 previously unreleased original songs.

Prior to her debut album release Song to a Seagull in March 1968, the Archives provides a fascinating chronicle of Joni Mitchell’s development as singer, guitarist, and above all, songwriter. Comprised of radio and television broadcasts, club dates, and home recordings on 5 CDs, we witness her transformation from folksinger of traditional and authored songs (“House of the Rising Sun,” Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee”) to becoming one of the greatest singer-songwriters of the 20th century. The collection includes early versions of iconic songs like “Urge for Going,” “Chelsea Morning, “Both Sides Now,” and “The Circle Game,” as well as over 25 previously unreleased original songs. Who is Peter Kaminsky? Peter Kaminsky taught at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and at Louisiana State University before joining the University of Connecticut faculty in 1993. His research interests include the music of Ravel, text-music relationships, popular music, structural principles in cyclic works, and, recently, performance and analysis and its pedagogy. He has published articles and reviews in Music Theory Spectrum, Music Analysis, Theoria, College Music Symposium, Music Theory Online, Theory and Practice, The Cambridge Companion to Ravel, and the Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie. Kaminsky is editor and contributor to Unmasking Ravel: New Perspectives on the Music (forthcoming, University of Rochester Press).

Who is Peter Kaminsky? Peter Kaminsky taught at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and at Louisiana State University before joining the University of Connecticut faculty in 1993. His research interests include the music of Ravel, text-music relationships, popular music, structural principles in cyclic works, and, recently, performance and analysis and its pedagogy. He has published articles and reviews in Music Theory Spectrum, Music Analysis, Theoria, College Music Symposium, Music Theory Online, Theory and Practice, The Cambridge Companion to Ravel, and the Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie. Kaminsky is editor and contributor to Unmasking Ravel: New Perspectives on the Music (forthcoming, University of Rochester Press). It is a Netflix release with an Asian/American cast that began around the time of the popular success of Crazy Rich Asians and K-dramas. In that sense, it is one of the latest forms of consuming racial minorities under liberal multiculturalism, marking the arrival of Asian Americans to the space of American evening leisure.

It is a Netflix release with an Asian/American cast that began around the time of the popular success of Crazy Rich Asians and K-dramas. In that sense, it is one of the latest forms of consuming racial minorities under liberal multiculturalism, marking the arrival of Asian Americans to the space of American evening leisure. Who is Na-Rae Kim? Na-Rae Kim is an Assistant Professor in Residence and Associate Director at the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, University of Connecticut. She specializes in transnational Korean literature, Asian American literature, history and theory of the novel, and Critical Asian studies. Her book project, Re-Turning Korea: Navigating Homelands in Korean American Literature, explores 21-Century Korean American literary imaginations of South and North Korea.

Who is Na-Rae Kim? Na-Rae Kim is an Assistant Professor in Residence and Associate Director at the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, University of Connecticut. She specializes in transnational Korean literature, Asian American literature, history and theory of the novel, and Critical Asian studies. Her book project, Re-Turning Korea: Navigating Homelands in Korean American Literature, explores 21-Century Korean American literary imaginations of South and North Korea.