The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has awarded a three-year grant of $750,000 to the University of Connecticut for the Humanities Institute to expand the New England Humanities Consortium (NEHC) Faculty of Color Working Group (FOCWG). The thirteen member institutions of the Consortium support programming in humanities fields such as history, politics, language, art, literature, and philosophy.

Following a 2018 Mellon Foundation $100,000 grant that permitted a pilot phase, faculty of color at NEHC member institutions created and led the Faculty of Color Working Group (FOCWG) for the purpose of increasing mentorship, community building, and dedicated time for scholarly production among faculty of color. Coupled with the development of the NEHC’s social media and publicity, through cross-institutional networks, research and teaching mentorship, and fellowships, the Mellon Foundation grant enables FOCWG to bolster faculty success across schools in the region and the nation.

The Principal investigator for the program is Michael P. Lynch, director of the UConn Humanities Institute, director of NEHC and Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor, Philosophy. Co-principal investigators are Melina Pappademos, director of the UConn Africana Studies Institute, associate professor of history, and director of the Faculty of Color Working Group; and Alexis L. Boylan, director of academic affairs of the UConn Humanities Institute and associate professor of art and art history and Africana Studies.

“With generous support from the Mellon Foundation, this initiative recognizes the environmental obstacles and, at times, outright hostilities to professional advancement that faculty of color face at predominantly white institutions. FOCWG seeks to address these institutional failures by enabling scholarly productivity and professional relationships, even self-care, as safe-guards for aggregated individual success,” says Pappademos. “The FOCWG challenges institutions to dismantle rather than uphold their inflexible structures designed and defended to advantage some faculty members over others.“

In addition to UConn, the consortium includes Amherst College, Colby College, Dartmouth College, Northeastern University, Tufts University, University of New Hampshire, University of Rhode Island, University of Vermont, Wellesley College, and Wheaton College.

The FOCWG provides an urgently needed pathway for faculty of color to navigate the particular challenges they face in academic life. As part of a large network of institutions, the FOCWG grant will develop collaborative fellowship and mentoring opportunities to produce outcomes unachievable by any single institution.

The core activities made possible by the grant include:

- Organizing an annual conference for faculty of color that will be the centerpiece of activities and outreach, which will include crucial professional dialogues on panel topics such as publishing, tenure and promotion and the challenge of transitioning into administrative roles. The conference will include pre-conference and post-conference interviews and surveys.

- Development of a mentorship program to identify and train senior faculty mentors throughout the New England Humanities Consortium to offer a resource for faculty of color at all stages of their careers, including those holding administrative positions, in the region.

- Establishment of The Mellon Faculty of Color Fellowship program, that will create opportunities for faculty to spend a year as a research fellow at another Consortium institution’s humanities institute or center contributing to crosspollination across the Consortium while furthering faculty’s individual research.

There will also be increased support for NEHC administrative functions including a separate FOCWG website, expanded social media presence and creation of an Instagram account to attract younger generation students and scholars, particularly those who attend liberal arts institutions.

In the words of Angela Davis, we are living in a time that we have never seen before. Americans are experiencing a myriad of emotions in response to the horrific events that are taking place in our country, from police brutality against Black bodies, racist effigies, lynchings of Black people, Covid-19 and its disproportionate effects on the health of Black and Brown people, and the lack of presidential leadership. The ugly truth is that some Americans have the privilege to be emotional about what is transpiring around us (e.g., white women throwing crying fits when confronted about a racist act). But Black women have a unique relationship with our emotions; an overt display of emotions by Black women, particularly negative emotions like sadness, anger, and doubt, is pathologized in the U.S. What I love about

In the words of Angela Davis, we are living in a time that we have never seen before. Americans are experiencing a myriad of emotions in response to the horrific events that are taking place in our country, from police brutality against Black bodies, racist effigies, lynchings of Black people, Covid-19 and its disproportionate effects on the health of Black and Brown people, and the lack of presidential leadership. The ugly truth is that some Americans have the privilege to be emotional about what is transpiring around us (e.g., white women throwing crying fits when confronted about a racist act). But Black women have a unique relationship with our emotions; an overt display of emotions by Black women, particularly negative emotions like sadness, anger, and doubt, is pathologized in the U.S. What I love about  Who is Shardé M. Davis?

Who is Shardé M. Davis?

In this brave new world of self-isolation, I have come to lose track of time. Time, or rather our concepts of the passage of time, are constructs that we animate and breathe life into, out of the necessities of our mortal lives. But to quote a Tralfamadorian from Slaughterhouse-Five: “

In this brave new world of self-isolation, I have come to lose track of time. Time, or rather our concepts of the passage of time, are constructs that we animate and breathe life into, out of the necessities of our mortal lives. But to quote a Tralfamadorian from Slaughterhouse-Five: “ Who is Siavash Samei?

Who is Siavash Samei?

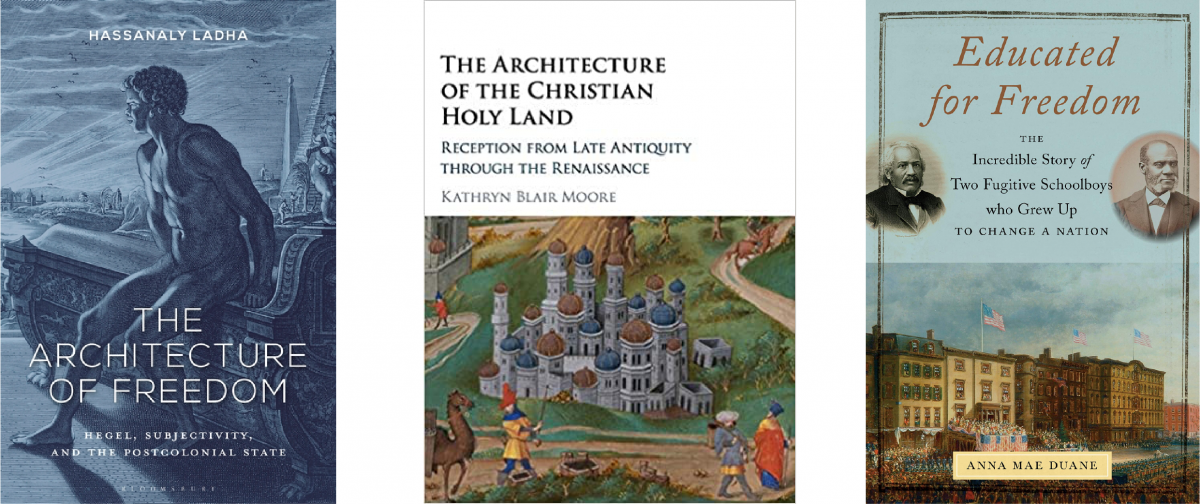

Kathryn Blair Moore, The Architecture of the Christian Holy Land: Reception from Late Antiquity through the Renaissance (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Kathryn Blair Moore, The Architecture of the Christian Holy Land: Reception from Late Antiquity through the Renaissance (Cambridge University Press, 2017) Hassanaly Ladha, The Architecture of Freedom: Hegel, Subjectivity, and the Postcolonial State (Bloomsbury, 2020)

Hassanaly Ladha, The Architecture of Freedom: Hegel, Subjectivity, and the Postcolonial State (Bloomsbury, 2020) Anna Mae Duane, Educated for Freedom: The Incredible Story of Two Fugitive Schoolboys Who Grew Up to Change a Nation (NYU Press, 2020)

Anna Mae Duane, Educated for Freedom: The Incredible Story of Two Fugitive Schoolboys Who Grew Up to Change a Nation (NYU Press, 2020)

There is only so much Netflix and Hulu one can watch and replaying Contagion and Outbreak are not the best antidote for COVID-19’s many anxieties. I suggest you find refuge in an

There is only so much Netflix and Hulu one can watch and replaying Contagion and Outbreak are not the best antidote for COVID-19’s many anxieties. I suggest you find refuge in an  Who is Fiona Vernal?

Who is Fiona Vernal?